Canada's State of Design: Past and Present 🇨🇦 📐

To build a thriving economy and raise quality-of-life, Canada must rediscover the strategic role of design. Here’s where we stand today.

In Note 2, we argued Canada urgently needs to prioritize design as a key lever for economic growth and innovation. Before design can help close our innovation gap, we need to ask a more fundamental question: do we understand what design is, how it works, or how it creates value?

If the blank stares 👀 👀 you get when saying you’re a designer are any indication, we still have some work to do. But what does that gap look like in measurable terms? Has Canada always struggled with design literacy, or is this a more recent decline? How do we stack up against our peers?

What do we mean by design?

Design is broad by nature and often misunderstood. It can mean the layout of a city, the structure of a service, the look of a logo. At its core, design is the deliberate act of developing better alternatives to move from problems to possibilities.

One of the most famous definitions is Herbert Simon’s from The Sciences of the Artificial (1969).

“Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.”

Canada certainly has its share of existing situations that need some improving but our understanding of design is often reduced to visual styling. While aesthetics are a vital component, it leaves design’s deeper economic and strategic value overlooked. Even in early conversations around Project Northward, it became clear that before we can inspire a design-first vision for Canada, we need a shared understanding of what design actually means.

With Project Northward, we group design’s potential national impact into three core pillars:

💰 Economic Impact

Design's ability to turn ideas into high-value goods and services, bridging invention and commercialization.

🌲 Quality of Life Impact

Design's role in shaping better systems, services, and environments for Canadians from healthcare to housing.

👋 National Identity Impact

Design as a cultural force, telling our stories, shaping how we see ourselves, and how the world sees us.

To reflect this strategic breadth, Project Northward proposes a working definition of design that is fit for Canada’s future:

“Design is how we intentionally shape the future — a process that bridges creativity with innovation to drive economic value, improve everyday life, and express who we are.”

If Canada is to fully realize this potential, we need to elevate our design maturity across emerging government policy, business, and society.

So where do we stand today?

Canada’s Current Design Reality

There’s constant talk about moving Canada’s economy "up the value chain," but our national approach to design is fragmented, under-utilized and under-funded.

Canada has no national design strategy.

While strong organizations like DesCan, RGD, ACIDO, and OAQ play critical roles, they remain provincial or discipline-specific, creating a tapestry of activity but without a cohesive national design ecosystem or strategy.

This fragmentation shows in our outcomes:

We start off on the wrong foot with R&D investment that is significantly lower at 1.7% of GDP compared to the US (3.5%), Germany (3.1%), and Japan (3.3%) (OECD Main Science & Technology Indicators, 2021).

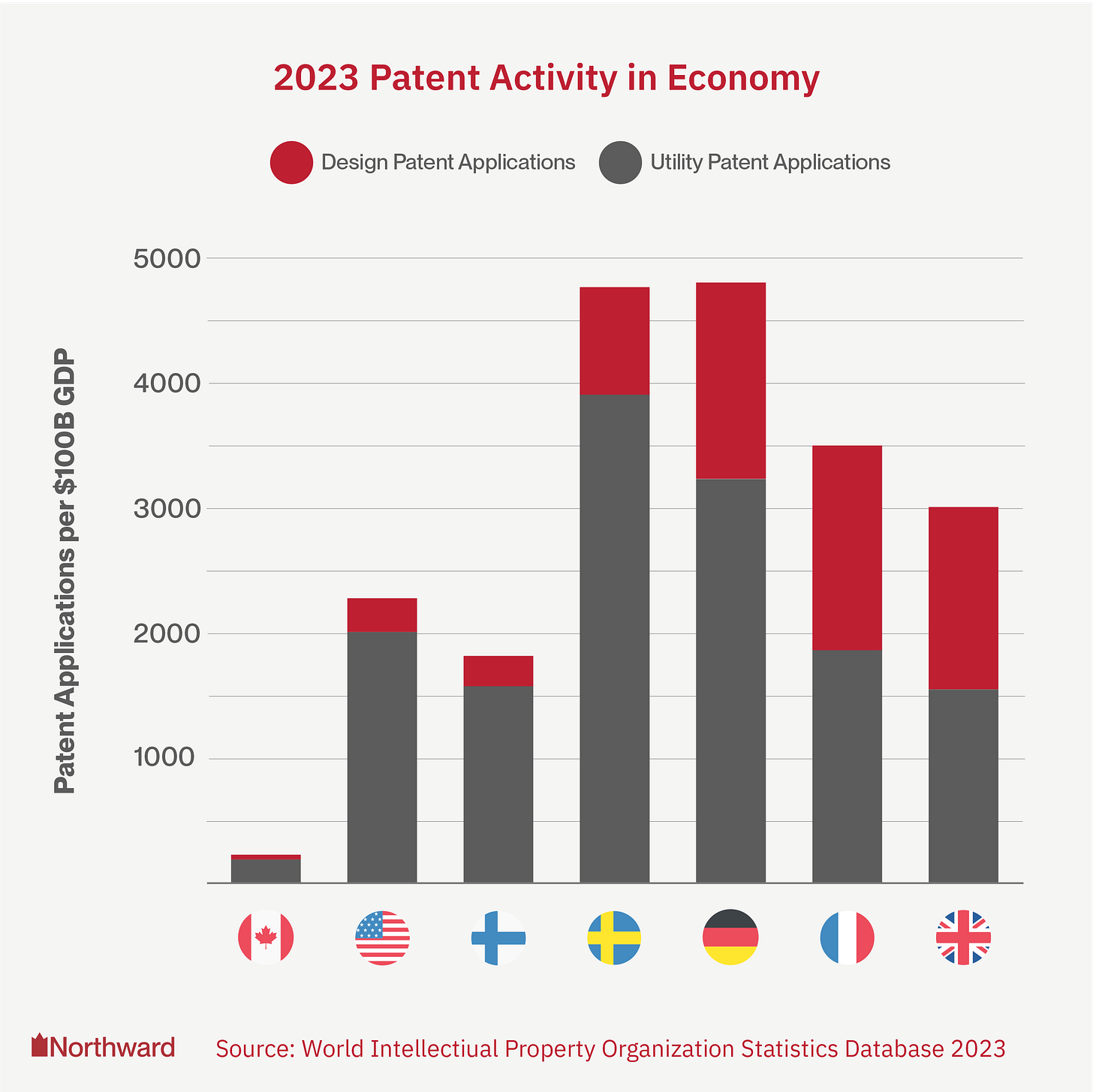

When we look at utility patents (general protection for new products/processes/materials) and industrial design patents (general protection for how something looks and a good proxy for quantifiable design activity), the picture gets worse and Canada trails far behind (you might need to zoom in 🔎).

In 2023, Canada saw 36 resident design applications per $100B in GDP, compared to 246 in Finland, 872 in Sweden, and between 1400-1600 in Germany, France and the UK.

When it comes to the ratio of design patents compared to general utility patents (a proxy for the share design activity makes up among general innovation) Canada sits at 0.19, far below nations like Germany approaching 0.5 and the UK and France, whose ratios are 4-5 greater and approach 0.9.

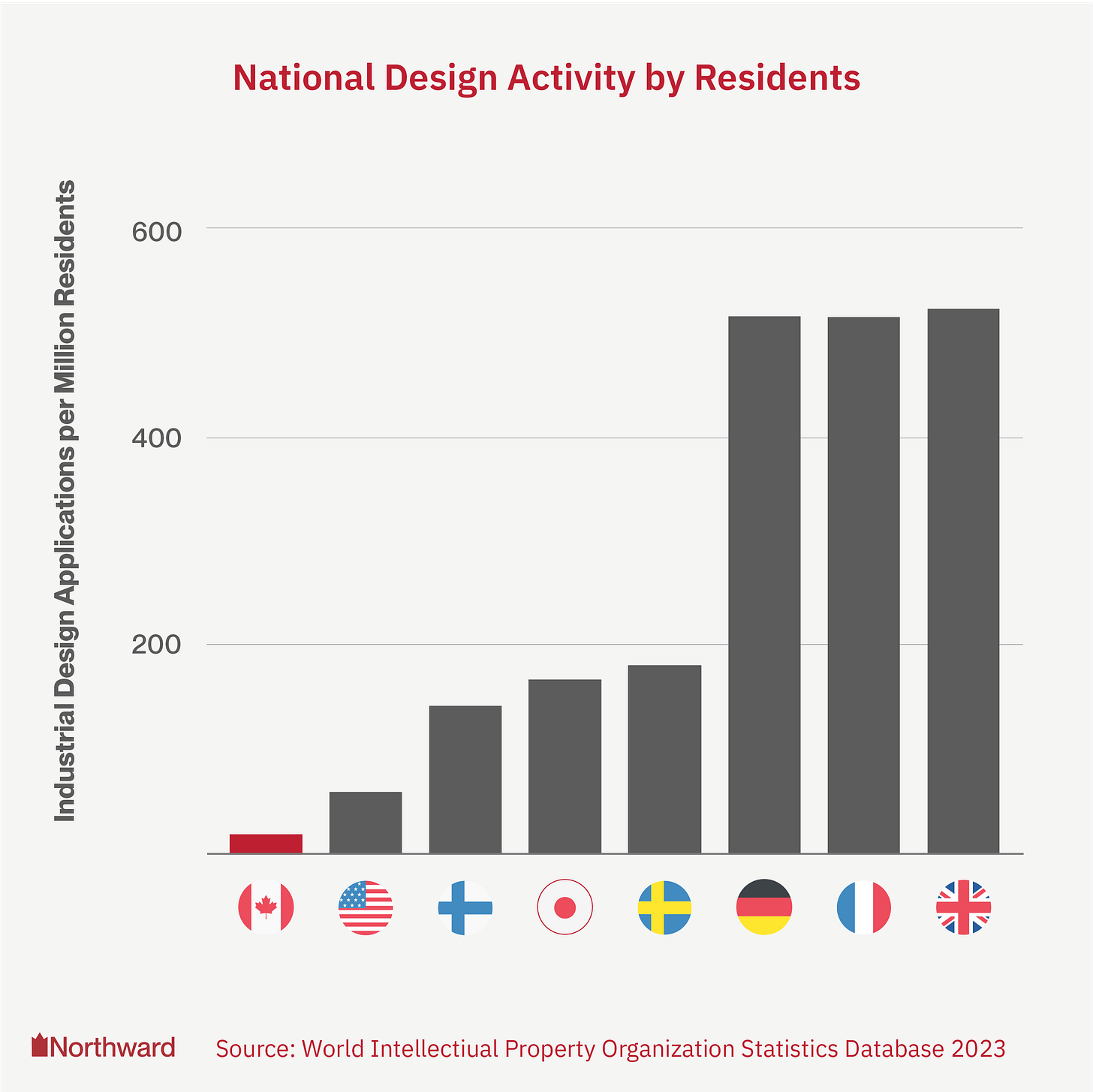

In 2023, only 19.7 industrial design patents were filed per million residents, while Sweden files 10x more—and Germany, France, and the UK file up to 25x more.

While industrial design patents are only one lens on design, the picture is clear: Canada is not deploying design at the level we need to compete in a world where we need to diversify our economy, move up the value chain, and improve the lives of Canadians.

Historical Context: When Canada Valued Design

It wasn’t always this way.

The federal government once saw design as vital to our national future. On June 1, 1961, the Diefenbaker government passed An Act for the Establishment of a National Design Council, with a clear mission:

“To plan and implement programs to create an awareness by industry and the general public of the need for good design.”

The National Design Council brought together all design disciplines like architecture, industrial design, graphic design, and more to help Canadian firms compete in global markets while ushering in a golden era of Canadian design.

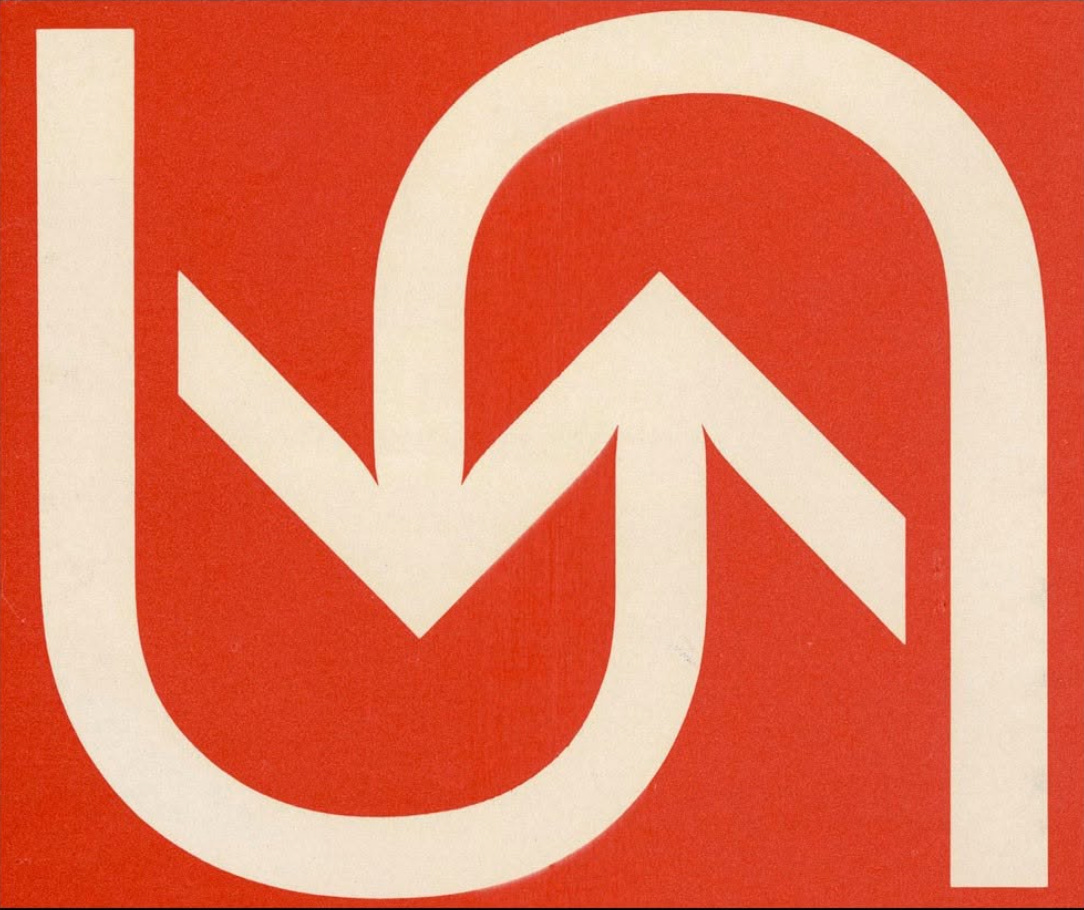

Logo for Design Canada, the National Design Council, designed by Allan Fleming in 1964.

This wasn’t just about branding. It was about economic capacity, competitiveness, and culture kicking off a golden age of Canadian design that captured the nation’s optimism and ambitions.

Clockwise from top left: Avro Arrow (1957-1959), Clairtone Project G Stereo (1964-1967), Northern Electric Contempra Phone (1967), Expo Chair (1967), Bombardier Ski-Doo Snowmobile (1959), Russell Spanner’s Lounge Chair (1960), Electrohome Apollo 860 Stereo (1967), CCM Mustang Bicycle (1960s)

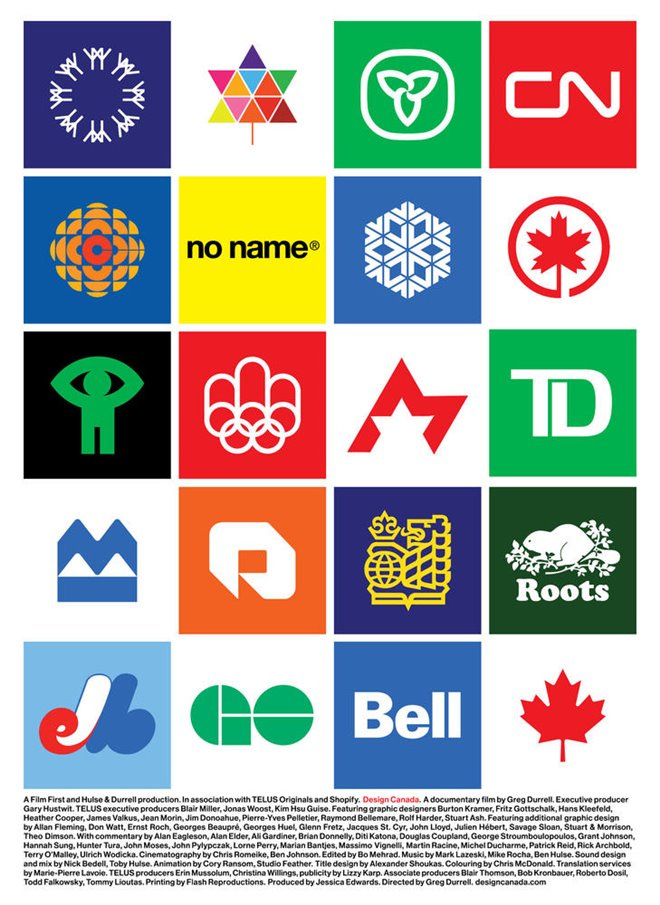

From a graphic design standpoint, the 2018 film Design Canada “a documentary film celebrating the golden era of Canadian Graphic Design” by Greg Durrell captures the magic and ambition of the era.

Movie poster for Design Canada featuring a collection of iconic Canadian logos designed from the 1950s through 1970s.

By the 1960s and ’70s, Canadian design had a seat at the table of nation-building.

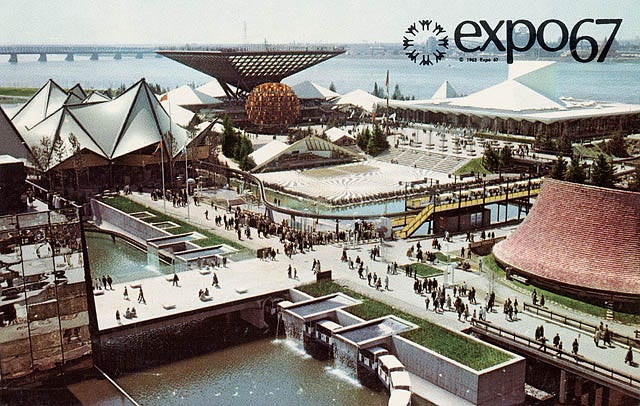

That spirit reached its high point with Expo 67, where Canada celebrated its centennial by putting design at the centre of its global showcase. It wasn’t just infrastructure but an expression of ambition. Canada was punching above its weight and designing a future others wanted to learn from.

Despite the successes, the momentum didn’t last.

By the mid-1980s, shifting economic priorities saw the federal closure of Design Canada, along with budget cuts and an economic turn back toward resource extraction industries that led to design losing its strategic seat at the national table.

This shift still affects us today, reflected in our underwhelming innovation performance and lack of strategic design leadership.

Global Lessons: How Other Nations Prioritize Design

If we look around us to our peers, we see a very different picture for how they see design as a national asset and engine for innovation, competitiveness, and national identity.

🇫🇮 Finland:

Design Forum Finland works closely with government ministries, positioning design as central to economic innovation, exports, and public-sector reform. Design is treated as essential, not decorative.🇰🇷 South Korea:

Korea’s Institute of Design Promotion (KIDP), aligned directly with the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy, strategically integrates design into national economic policy. Design is explicitly stated as "essential in the knowledge-based society."🇬🇧 United Kingdom:

The UK’s Design Council partners closely with government and industry to embed design across manufacturing, public services, and innovation programs, recognizing design’s strategic value for economic and social improvement.🇸🇪 Sweden:

The Swedish government leverages design to address sustainability, innovation, and social transformation. The Swedish Design Movement explicitly positions design as "a method for innovation and problem-solving."🇩🇪 Germany:

The German Design Council, established by the Bundestag in 1953, advocates for design as fundamental to industrial competitiveness, economic growth, and national branding. It supports Germany’s export-driven economy through strategic design initiatives.

Until Canada’s immature and fragmented approach changes, we’ll fail to unleash the full potential of design as we find ourselves on the brink of a new era of nation building.

Designing Canada’s Path Forward

In Note 2 we made the case for how design is a vital economic and quality of life multiplier.

In Note 3 we’ve seen just how little we’re using it and how far we’ve drifted from a time when Canada treated design as a tool of national ambition.

Now, in a moment where nation-building is back on the table and Canada is rethinking its place in the world, we need to reintroduce design as a comprehensive national tool, for economy, quality of life, and identity.

🇨🇦 Let’s rebuild a Canadian design-first vision that’s ambitious, modern, and proudly our own.

If you believe in that future please join Project Northward and share this post far and wide. Designing Canada’s path forward starts with believing we can.

👉 Up next we spotlight the designers, builders, and visionaries leading this charge.